Every .gov website, no matter how small, should give its visitors a secure,

private connection. Plain HTTP (http://) connections are neither secure nor

private, and can be easily intercepted and impersonated. In today’s web

browsers, the best and easiest way to fix that is to use HTTPS (https://).

Now, a number of government websites have taken a step further and are becoming the first .gov domains hardcoded into major web browsers as HTTPS- only.

This means that when visitors type “notalone.gov” or click a link to http://notalone.gov, the browser will go directly to https://notalone.gov without ever attempting to connect over plain HTTP. This prevents anyone from getting a chance to intercept or maliciously redirect the connection, and avoids exposing URLs, metadata, and cookies that would otherwise have remained private.

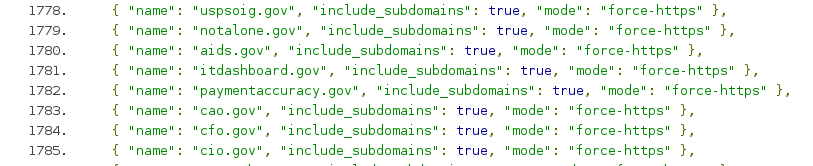

18F worked with a number of government teams to help submit 19 .gov domains

to be hardcoded as HTTPS-only:

- The Federal Trade Commission prepared the Do Not Call Registry, as well as their consumer complaint system and a merger filing system, by submitting donotcall.gov, ftccomplaintassistant.gov, and hsr.gov. The FTC has also written about their work on these domains.

- The Inspector General for the US Postal Service submitted uspsoig.gov (which includes various sensitive complaint forms) after moving entirely to HTTPS.

- The AIDS.gov team submitted their domain after moving the main website and each subdomain over to HTTPS.

- The Administrative Conference of the US submitted acus.gov after moving to HTTPS while relaunching their website.

- At the state level, the District of Columbia legislature submitted dccode.gov as part of its launch.

- The Federal Register submitted federalregister.gov, a fully HTTPS-enabled website since 2011.

- 18F chipped in and submitted notalone.gov, which used HTTPS from the start.

- The OMB MAX team worked with the White House and the General Services Administration to prepare the website for the Federal CIO Council and a number of other websites and redirect domains: cio.gov, cao.gov, cfo.gov, max.gov, itdashboard.gov, paymentaccuracy.gov, earmarks.gov, bfelob.gov, save.gov, saveaward.gov.

To be clear: the above domains are not the only .gov domains that use

HTTPS. Many others do. The above domains have taken the extra step of

verifying that all their subdomains use HTTPS, and are comfortable telling

browsers to just assume this going forward. This will take effect in Chrome,

Firefox, and Safari over the course of 2015.

There are many more .gov domains, but we hope this contribution is the beginning of something bigger.

Read on for more about why HTTPS is important, how to reliably force HTTPS, and how to submit your own domain to browsers.

What HTTPS does

We’ve written previously about why HTTPS is good for .gov websites and visitors, no matter how important the website may be. To understand why, it helps to understand the information that HTTPS protects.

When you visit a website, your computer connects to the website’s computer. This means you send information about yourself sprinting across the internet at the speed of light, passing through the computers of companies and countries from all over the world that sit between you and the website’s computer. That’s how the internet works: a sprawling, unpredictable network of computers under the control of potentially anyone.

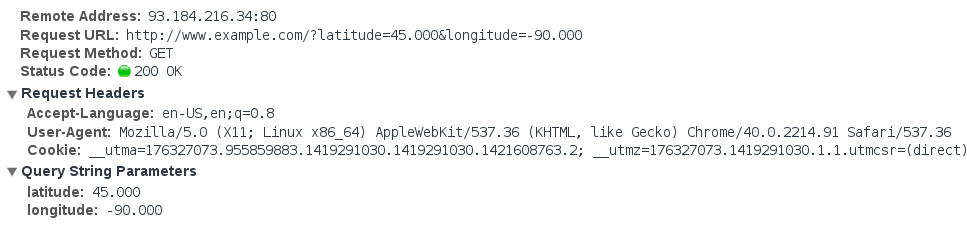

When you connect over ordinary http://, it’s like sending a postcard in

the mail, where every computer in between you and the website gets to see

your information:

That includes cookies, the browser you use, and any other data the website asks you to send (in this example, your location).

And because it’s like a postcard, any computer in between you and the website

can freely erase, change, or add information on the postcard (imagine it’s

written in pencil). In fact, because insecure http:// connections are so

common, this happens all the time and it’s often invisible to the ordinary

user.

When you can connect over https://, it’s like sending a locked briefcase

that only the website’s computer can open. IP addresses and a domain name are

all that the internet’s computers get to see:

IP addresses and domain names do still reveal some information, but it’s the bare minimum necessary to make the connection.

HTTPS guarantees that the connection between you and the website is secure and private.

Tightening up HTTPS with Strict Transport Security

Even after a website turns on HTTPS, visitors may still end up trying to connect over plain HTTP. For example:

- When a user types “dccode.gov” into the URL bar, browsers default to using

http://. - A user may click on an old link that mistakenly uses an

http://URL. - A user’s network may be hostile and actively rewrite

https://links tohttp://.

Generally, websites that prefer HTTPS will still listen for connections over HTTP in order to redirect the user to the HTTPS URL.

So when a visitor clicks a link to http://dccode.gov, the website will allow

the connection for just long enough to tell the visitor’s browser to go to

https://dccode.gov.

However, that redirect is itself insecure (it’s on a postcard), and is an opportunity for an attacker to capture information about the visitor, or to maliciously redirect the user to a phishing site.

Any website can protect their visitors from this scenario by instructing browsers to only connect over HTTPS using an open standard called HTTP Strict Transport Security, or HSTS.

Turning on HSTS means adding a Strict-Transport-Security HTTP header to your website:

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000;

Any browser that supports HSTS that sees

that header will from then on refuse to issue an http:// request to that

website, issuing an https:// request instead.

HSTS greatly increases the security and privacy of a website, and is a very easy add-on to HTTPS.

Its main weak point is that the visitor’s first visit to the website is not protected (it’s still a postcard!), as the browser needs to visit the website once in order to receive the HSTS instruction.

An HSTS Preload List

To solve the “first visit” problem, the Chrome security team created an “HSTS preload list”: a list of domains baked into Chrome that get Strict Transport Security enabled automatically, even for the first visit.

Firefox and Safari also incorporate Chrome’s list, as will newer versions of Internet Explorer.

While a giant list may sound crude, it’s a simple solution that many of today’s most popular websites (including Twitter, Facebook, Google, and GitHub) use to protect your visits.

The Chrome security team allows anyone to submit their domain to the list, provided you meet the following requirements:

- Enable HTTPS on your root domain (e.g.

https://donotcall.gov), and all subdomains (e.g.https://www.donotcall.gov). - Your website should redirect from HTTP to HTTPS, at least on the root domain.

- Your root domain should turn on Strict Transport Security for all subdomains,

with a long

max-age, and apreloadflag to indicate that the domain owner consents to preloading.

If you check out the HTTP headers sent by the .gov domains above, you’ll see

that they all include the following header:

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

So in short, if you want to add your domain to the list: force HTTPS on the whole domain, add that header, and submit the form.

Moving forward

Obviously, you can’t hardcode the entire internet into a big list.

But the .gov space, by comparison, is quite small. Perhaps someday we’ll be

able to just delete every individual .gov domain from the list and replace

them with one entry: *.gov.

In the meantime, the internet’s governing bodies are clearly stating that encryption is the future, and a lot of people are working to make HTTPS simpler to deploy. It’s becoming easier to imagine a future where web browsers treat HTTPS as the norm, and warn visitors away from plain HTTP entirely.

Finally, a big thank you to the civil servants across government who took the

time to prepare their .gov domains.