When I joined the code.gov project, I had just over a month to make an impact on the project. The most pressing work seemed to be defining a software metadata schema — a way for agencies to format the details of the software they’ve built.

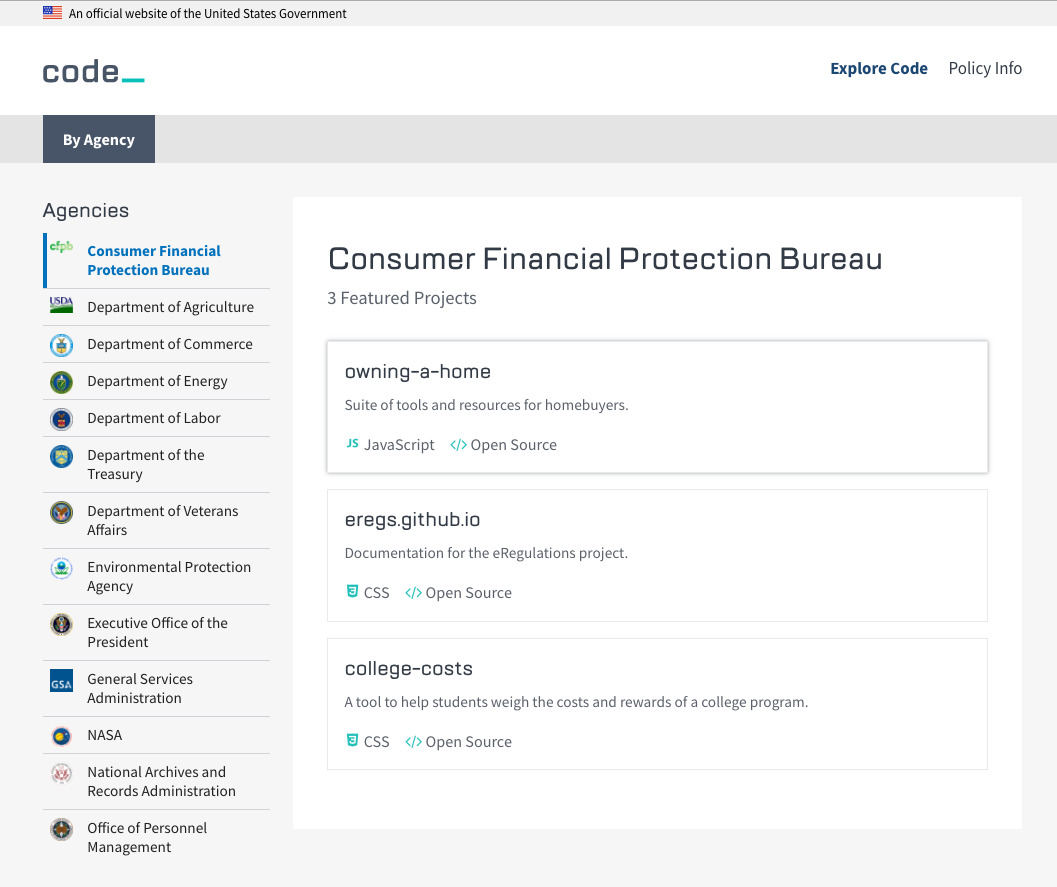

In August of this year, the Federal Source Code Policy was signed. It requires federal agencies to, among other things, inventory their custom software and make the inventory available for consumption and display by code.gov. This will allow agencies to reuse and collaborate on software. You can read more about the policy on code.gov.

The urgency to define the schema was driven by a 120-day deadline for agencies to use the schema to prepare their enterprise code inventories. We needed to define the schema with plenty of time for agencies to digest and adopt it.

Something else we were keenly aware of was that we were defining something agencies would be required to comply with, adding more work to their already formidable workloads. The schema needed to be easy to implement and understand, or else we would jeopardize adoption of the policy.

When I joined the project, I was able to start with a draft schema from one of my colleagues. I’m new to the art of schema specification, and this led me to the decision I think made all the difference to the outcome of the schema definition — I decided to bring in as many outside voices and ideas as I could. I came to quickly view my role as the curator of the best thinking available.

I started by putting a call out to a handful of my 18F colleagues whom I knew had more experience in the area than I did and asked for feedback. Admittedly, at this point I was reluctant to put what we had out into the world as I felt it wasn’t polished enough, but with some gentle encouragement from others on the project, we published our first GitHub issue calling for feedback.

I’m very glad we created that issue when we did. We received an amazing amount of high-quality feedback from the community, including both agency folks and the public in general. People brought up a great point, that we weren’t the first people to think about defining such a schema. After reviewing and prototyping a couple, we settled on an approach based off of this civic.json, originally defined by BetaNYC and extended by Code for DC and DC government employees.

{

"agency": "DOABC",

"organization": "XYZ Department",

"projects": [

{

"name": "mygov",

"description": "A Platform for Connecting People and Government",

"license": "https://path.to/license",

"openSourceProject": 1,

"governmentWideReuseProject": 0,

"tags": [

"platform",

"government",

"connecting",

"people"

],

"contact": {

"email": "project@agency.gov",

"name": "Project Coordinator Name",

"URL": "https://twitter.com/projectname",

"phone": "2025551313"

},

"status": "Alpha",

"vcs": "git",

"repository": "https://github.com/presidential-innovation-fellows",

"homepage": "https://agency.gov/project-homepage",

"downloadURL": "https://agency.gov/project/dist.tar.gz",

"languages": [

"java",

"python"

],

"partners": [

{

"name": "DOXYZ",

"email": "project@doxyz.gov"

}

],

"exemption": null,

"update": {

"lastCommit": "2016-04-13",

"metadataLastUpdated": "2016-04-13",

"lastModified": "2016-04-12"

}

}

]

}

We made a call for a second round of feedback to verify that there were no major issues in the schema we were proposing. I recognized that a schema defined in a month largely by someone new to the policy would certainly not be perfect, and instead wanted to focus on a solid foundation that could be extended. I hope we accomplished that, and you can be the judge by checking out the documentation on code.gov.

We were able to find success within the aggressive timeline because we relied on the wisdom of others with more domain knowledge and technical expertise to guide us. Instead of coming up with our own custom approach in isolation, we asked for input from our users and the public. This has helped our agency partners feel more engaged and has created a better end product. We were able to leverage something that already exists, and verify that it met our users’ needs, all within a month!