Large software systems are hard, and in government we’re tasked with building large systems to manage complex benefits and processes. Often those mandates arrive on the back of a failing legacy system.

The problem with creating large systems is that before we even start building we worry about how everything will work. There are so many razor sharp edge cases to consider. As the planning process grows, so does the complexity. Deadlines slip before the first line of code is written, and the likelihood of failure escalates.

An agile workflow has the benefit of allowing us to try out our ideas before committing years of time and money. Agile development does not solve the dilemma of how to build big. In fact, many critics of agile process see the incremental build process as a way of postponing design and architecture to the point of crisis. Agile is not architecture; it’s a planning process.

Architectural flavors

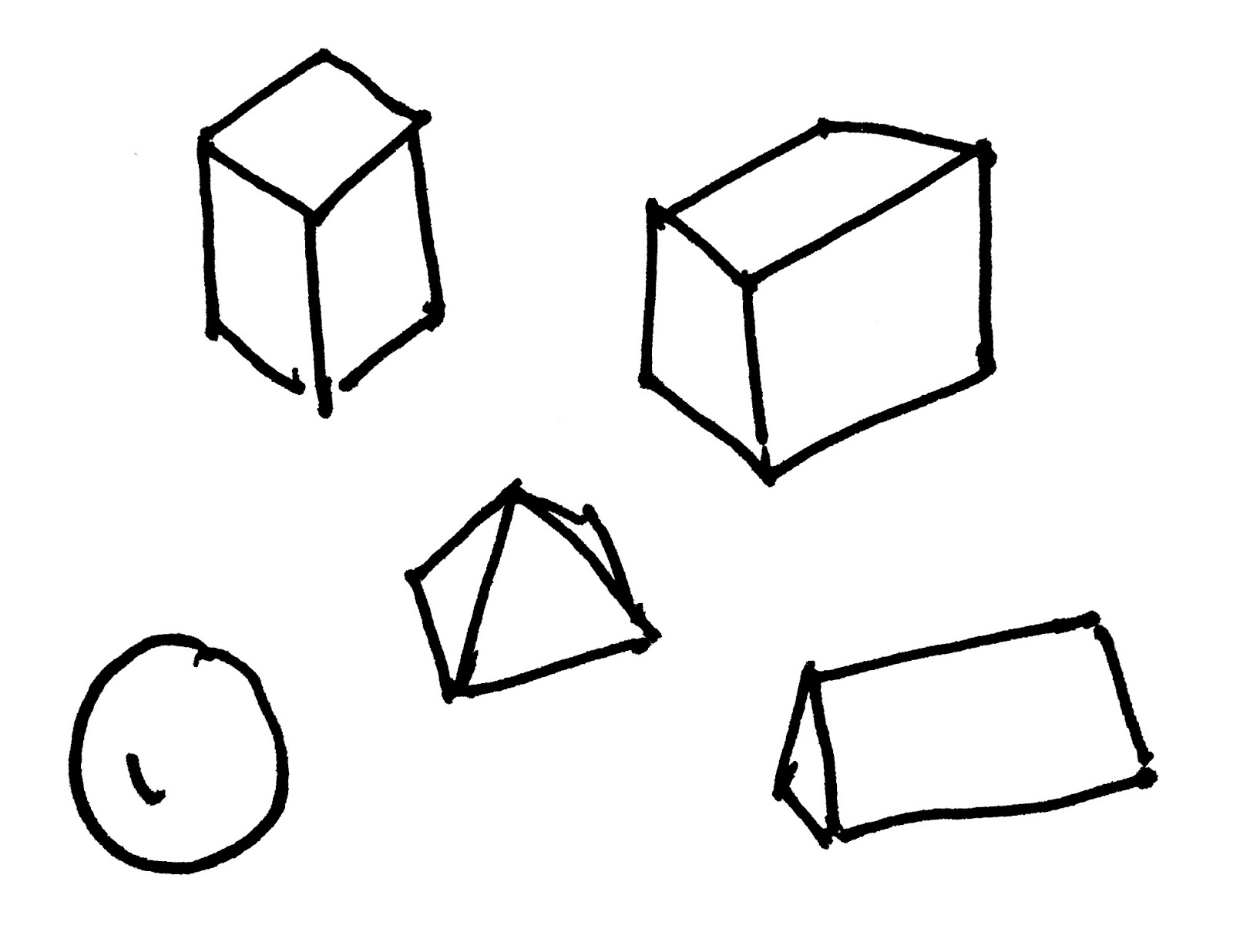

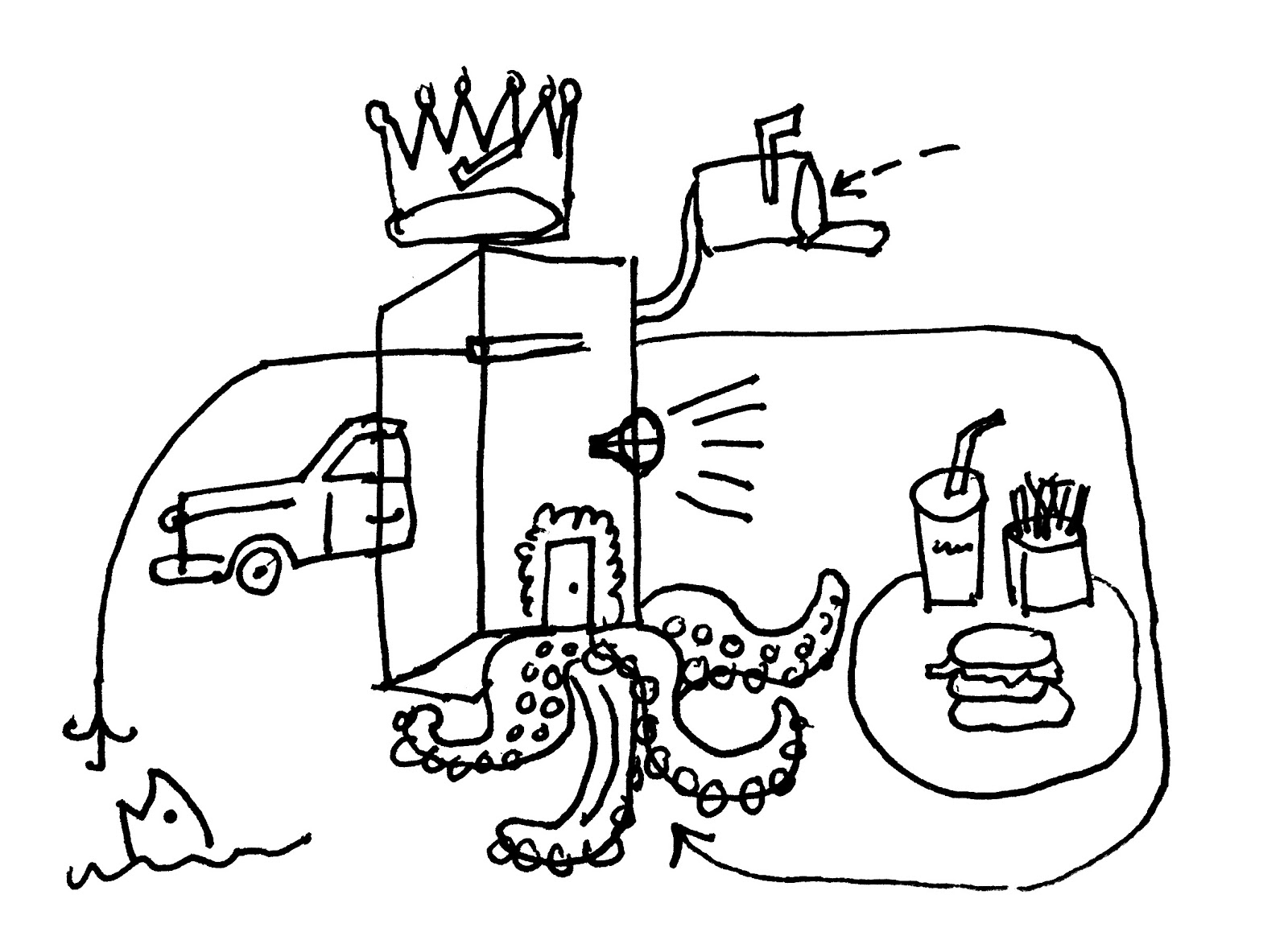

Big software systems happen in two major varieties: monoliths and services. Before diving into the best way to mix and match these patterns, I want to describe each of their growth patterns and risks.

A monolith is one big application. Monoliths are easy to understand because everything is in one place. This is especially true in the beginning when the application is small. The user interface should be seamless and consistent because it’s all one application, and the files that an engineer needs to get work done are all in the same project.

This is a contrast to service-oriented architecture, which divides applications into smaller pieces. Sometimes these services are distinct user experiences such as an admin interface or an application focused on email; other times the services are smaller helper modules that work behind the scenes. For example, I’ve built services that send emails, process images, and do sentiment analysis on text. Application users would see the fruits of these microservices within a holistic user experience, but would have no direct knowledge of the separation of services.

In a service architecture, an engineer might need to change several different projects just to get a small feature out the door. A poorly designed services architecture will put a burden on application users. They may notice awkward graphic transitions as they move between applications. Sometimes they’ll be forced to sign into many applications.

Given that monoliths are simpler than services, why would we ever consider a service-oriented architecture?

The answer is scale. While a monolith starts out as a simple and sleek application, as the number of user types and features in the application multiplies so does the product and code complexity. Radically different ideas get packed into the same bloated application, and soon the developers have a hard time finding the code they need to get their work done. They have a hard time managing the complexity and the bugs.

Monoliths that grow too large stagger under their own weight. Product teams witness this failure as reduced productivity. The amount of time fighting bugs increases while feature releases drop. New features risk the introduction of new bugs very far away from the new release. End users lose confidence in the system as data becomes inconsistent and page load times increase.

Monolithic architectures typically have a hard time scaling engineering talent too. As a large number of developers all work on the same system, they create more and more conflicts as they change the same areas of the code. Organizations often use service oriented architecture as a way of separating into discreet engineering teams.

From the descriptions of monoliths and services, it’s clear that monoliths shine when small and services are good for larger more complex systems. There is one significant issue services bring to the table: integration. Many service-oriented architectures were theorized as a graph and each component was built in isolation. Once all the individual teams come together, they realize that their systems don’t communicate. Each small system may be perfect at what it does, but it isn’t building towards the whole system.

Rescue work can be done to make the whole system communicate, but these efforts can’t improve the damage to the user experience created by building these overly abstract and unintuitive components.

Start small, make it end-to-end

There is a path through these architectural choices. Getting back to agile practices, we can reduce risk by starting small and releasing something usable quickly. The first thing built should not be a small module in a service-oriented universe. A small user flow should be built end-to-end as a small monolith.

Finding a small, isolated, end-to-end flow is deceptively difficult. Part of the difficulty is that it can be hard to believe the software will have any use until the whole vision is implemented. Suspending disbelief about value is an important first step to finding something small and accomplishable. It’s important to have experienced product managers who have mastered the skill of finding a minimal viable product.

Once the team is willing to try something small, there are two good approaches to finding that end-to-end flow:

-

Look to the place of highest pain. Often users are in a good deal of discomfort because they don’t have the solutions they need. Focusing on the highest pain point focuses on the highest potential value. The team then has to repeatedly cut scope to get to something very small. That very small end-to-end application flow will not solve all the pain, and it may not even put a bandage on it. Have faith and build incrementally.

-

Find the easiest thing. Instead of focusing on pain, the team could also try to find low hanging fruit. This is a way of getting value via speed and simplicity. The risk here is that there will be a small jumble of unrelated features. Your product team has to build value by building towards a whole.

Build incrementally, divide wisely

Once an application has been started as a small monolith with a single end-to-end flow, the team needs to keep developing the application driven by highest impact. Prioritizing to keep the highest value at the top of the work queue ensures the product doesn’t decay. Keeping the system as simple as possible is important both for the user experience and the code quality.

As the application grows, there will be indications that it needs to divide into services to avoid becoming a big, unwieldy monolith. It’s easy to get abstract in thinking about services, but the division of a monolith into parts should be driven by product and design. Dividing different applications by collections of user flows is safer than dividing via abstract programming concepts.

Here are a few examples of things that might trigger extracting a new application or microservice from a monolith:

-

There is more than one user type, and the needs of the different users are becoming separate sections of the application. The quintessential example of this is an admin section of an application. In order to get into that section, you have to have special permissions. What you do there is special and requires authorization. A separate administrative application would reduce complexity and likely increase security.

-

The application starts to naturally develop into sections. In a product that manages benefits, different sections of the product will naturally develop. An agency worker might see an area for application in progress, messages from applicants, and decisions from the agency. Tabs or some other navigation might show up to separate these sections. Sectioned off functionality makes a good dividing line for extracting applications.

-

There are small functions that can be extracted into microservices. As an application develops there are dozens of functions that it takes on. Some of these form the backbone of the code. Others are important to users, but exist on the periphery of the application and can be extracted. For example, an application may take a user photo and crop it to a square. There can be a separate microservice responsible for that work. A poor candidate for a service extraction would be a data-caching layer. Data is central to applications, and this kind of extraction is like removing the beating heart from the system.

As the application starts dividing into services, the whole project can move faster. More teams can be brought on to work on sections as they’re extracted. The product owner needs to assure that the system remains integrated and focused on the whole experience and value.

Focus on product practice, not engineering

Usually we think about software problems as being hard engineering problems. Scale is hard, but not in a computer science way. Scale is hard in a product way. Figuring out which things should be done first is a product problem. Communicating with end users about the rollout of a section that does not yet do everything they need is a product problem. Even negotiating complexity between program managers and engineers is a product problem.

In the world of software development, we have an impressive assemblage of knowledge about computer science problems, but we’re just starting to understand the product development practices. Product development is not the same as project management, which is concerned with schedule and budget. I think of product management as sorting out the question of “what” should be built. That work is always in the service of the larger goal of creating impact. The product manager’s job is to work with program managers, stakeholders, end users, and software teams to deliver the greatest impact at scale. Whether you’re in the monolith stage, or dividing your software into parts, product thinking and product work is integral to making the right thing.

As we grow and divide large systems, we need to avoid abstract diagrams and instead focus on product. The best way to build big is to start small. The best way to scale is to focus on user needs and divide at their boundaries.