Governance and strategy can be extremely hard to implement for organizations that take care of large and complex systems. Top-down structures can move slowly, smother innovation, and have unintended consequences when they are implemented months or years later.

Conversely, a lack of structure can lead to inconsistencies that make working across the organization difficult, because interoperability can be undervalued the further you are from central decision making. You can also get very inconsistent results, with some projects falling behind standards. We have compliance standards in government that we need to document to show we are making choices and changes responsibly.

The added value of using agile and DevOps is that:

- Stakeholders, collaborators, and implementers agree on measurable outcomes

- More information and context for decisions when they are getting made

- We can make course corrections quickly, with fewer bureaucratic bottlenecks

Traditional change control board

Traditional change control boards and most software lifecycle management approaches in government were born in the age of waterfall processes. As software development practices evolve, change control processes that were not designed for agile product development processes often become a major point of friction.

Detailed planning up-front: With waterfall processes, project planning happens first— you must anticipate all needs that the project will have in the future through requirements gathering. Absolutely everything needs to be documented during the requirements phase since the deliverable is often handed off to an entirely different implementation team. The documentation can vary widely in quality, depending on who produces and reviews it. This really long report needs to contain everything that might be needed in the future, because changing course after you start will be hard and costly. Making thousands of small decisions, without having prototypes to test your conclusions with actual users is a Herculean task that often fails.

Traditional change control boards use these large documents as their main artifacts for review. Though it may feel safe at the time, requirements gathering is a very risky and flawed practice. It is impossible to anticipate the needs of all your users and stakeholders, and business needs and policies will undoubtedly change. The bigger the engagement, the more likely you won’t be able to plan or anticipate everything.

Anticipating user needs: Often requirements fail to take into account every eventuality, the needs of every user group and how needs and policies will change. People are blamed for not planning well, instead of evaluating the planning process. Since no one is omniscient, this can be an impossible task. The bigger the project, the greater likelihood that something doesn’t go as planned. Since everything was planned up front, these bottlenecks can create ripple effects, magnifying even small forecasting errors.

Security as an afterthought: Security is also often considered at the beginning of the project but then implementation and checks for security are left until the very end. At that point making corrections can be cumbersome and these massive reviews can lead to lots of back and forth communication.

Stakeholder driven decisions: All decisions are made upfront by stakeholders. They have to take a long time because there are a lot of requirements and they have to think of all contingencies in advance.

Rigidity: More flexible systems tend to adapt better to chances. The worst project results usually come from the most rigid structures that don’t have good contingencies for when things don’t go to plan or when the unexpected throws a wrench into the grand plan. Failures are generally blamed on not enough planning or on poor planning, but the people working in these traditional ways are already very good at planning. Change control boards are usually filled with smart, highly-capable people, making decisions the best that they can in a broken framework. This isn’t a problem that can be solved with better up front planning.

Once there is a plan, vendors spend years implementing all the requirements.

Finally, you get the thing you asked for years ago, but not the thing you want now. Adjustments can be hard to make and you might have to start this process from the beginning.

Agile and DevOps case study

Agile is a way of quickly reacting to the demands of your project where DevOps (which combines software development and IT Operations) is a methodology for building infrastructure and applications that is able to adapt and change quickly. Using these methods, you can avoid many of the pitfalls of traditional waterfall practices described above.

Getting started

- Outline the scope of the project, what kind of data the project needs and what technical stack it will run on. Define the product not by final goals, but the leanest version of that product that will be useful. Consider what future features may be useful when making decisions but first focus on core functionality. Here is a resource for setting product vision and strategy.

- Check in with enterprise architecture teams, security teams, the operations team, and PRA and privacy office contacts if you are planning to use forms or house data. Look for other similar projects in your agency: are they happy with their product? What would they change? Getting buy-in from a wide range of people early can save you time later.

- This is a good time to agree on some mission and quality outcomes to strive for. Create goals such as security scan protocols that all releases will go though. Set up bi-weekly or monthly accessibility checks with an accessibility expert. Be precise about the kind of milestones that need to be met before personal data is added to the system. It is more important to frame these as outcome-oriented goals and not process goals. You want the flexibility to improve your processes, but make sure as processes change the outcomes for standards are consistent.

- Start by approaching some of the riskiest parts of the project. Tackle whatever might make the project fail first. Are there simple ways to test the viability of your project? These could be mock-ups, a google form, or another way to quickly confirm you are using the right strategy to solve the right problem. Next, think about deployment or a tricky integration.

Example workflow for project growth and maintenance

Project roadmap

Build consensus about the problem you are solving, then break down that problem into smaller problems. These tasks will eventually become features but it is important to not commit to solutions too early. You want room to innovate and find better ways of doing things. If you start translating what you want into features too early, you will likely miss critical opportunities to improve your processes.

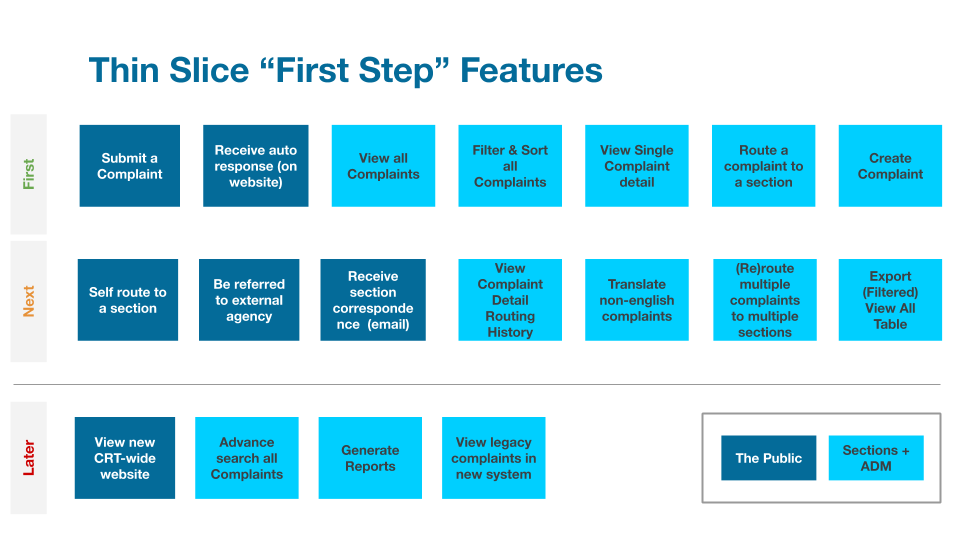

As an example of an early roadmap from the civilrights.justice.gov site, 18F worked with the Department of Justice (DOJ) Civil Rights Division to improve the way the Civil Rights Division engages with the public. The previous website made people navigate through a maze of options to report civil rights violations. 18F’s approach consolidated seven unique email addresses, four webforms, over fifteen phone numbers, and nine mailing addresses into a new portal that dramatically eased the burden on victims of civil rights violations to identify the proper reporting channel, while also maintaining the mail and phone pathways that we knew were still important.

To achieve these goals, we needed to understand the needs of various users and break up the big picture into small manageable pieces of work. Each piece added value to the product and each iteration produces working software.

Below is an example roadmap from the project that shows how we broke up the problem into smaller pieces and prioritized. While this roadmap describes the features to be developed, an underlying backlog incorporated security, compliance and accessibility tasks to contextualize feature development.

Roadmaps are a great starting point but it is important to remember that they are not a list of requirements—the point of agile development is to make changes as you learn more about your users, problem space, and the other realities of your project. The relative importance of any particular feature may not be what you thought after you implement some and learn more about your needs.

Roadmaps need to be regularly updated and renegotiated as the project develops to make sure you are building the right product. Revising roadmaps on a quarterly basis can work well, but the exact timing depends on project needs.

User stories

Each milestone in your roadmap is high-level and can be implemented in many different ways. The first step in breaking down those higher-order outcomes is to create user stories that describe the outcome someone using your product or process is looking for and why they want that outcome.

As an example, a user story from our project:

As a public user, I want to know that my complaint was submitted so that I can complete the process and save the information for my records.

If you are new to user stories, we have a blog post describing the process for mapping user stories.

There are several agile methods for breaking user stories into manageable workflows for your team, including SCRUM and kanban which are commonly used by development teams. The most important considerations when choosing a method for your team are:

- You frequently test what you build with people that will eventually use the product or service.

- You change your plans based on what you learn from testing.

- You build things as early and as lean as possible so you don’t get too far ahead of your user feedback

For more, you can check the 18F Practices for a deeper introduction to agile.

If you are new to agile, there are a couple common pitfalls to watch out for:

- Agilefall: A common trap for teams new to agile is adding more meetings with agile-sounding names and sprint cadences while keeping waterfall development processes without the agile practices of regularly testing and iterating based on feedback. This is referred to as “agilefall” and typically leads to poor results and makes everyone less happy with the process and outcome. If this sounds familiar, you should read our blog post “You might not be as agile as you think you are”.

- Lack of structure: The other pitfall can be chaos. Agile isn’t a lack of planning, it is breaking down planning into smaller chunks and doing that planning as needed. While you might not yet know the full solution to a problem, your team should have a shared understanding of what your approach will be, who will be doing what, and when you start working on it. I was once on a call where someone answered a concrete question about their product security, which should have been in their roadmap with “We are sculpting a David right now, we haven’t chiseled out those details.” That kind of response lacks communication about what you hope to achieve, the scope of your project. Collaborators and stakeholders will be hesitant to adopt new ways if you can’t explain them. You should be able to identify the plan for what you are building and how you want to approach the problem. You can make changes to the plan, but there should still be a general plan. That plan needs to be socialized early across teams that you collaborate with.

DevOps

Now you are in the part of the agile process where building can start. This is where we get the added benefits to governance from DevOps (also called DevSecOps—which stands for development, security, and operations—if you are in government).

DevOps has a few main components:

- Cross-functional collaboration

- Automation

- Smaller, more frequent deployments

- Testing to ensure quality of application, infrastructure and security

Cross-functional collaboration

Traditional operations will have developers write some code and then “throw it over the fence” to people in operations. These hand-offs can be tricky even at the best of times. Context can be lost in those transitions. When problems occur, it can be hard to tell which side of the fence a solution should come from. In contrast, sharing responsibility and working together from the start will take time to coordinate, but you get that time back when problems are easier to locate and the friction of reaching across teams is removed.

Automate

Automation of software deployment improves outcomes, by making processes repeatable and predictable across environments and freeing up time for more important tasks. Manual deployments take a lot of time and are susceptible to human error, even when run by skilled experts.

Mitigate risk

DevOps is aimed at reducing the risks of system downtime and failures when you deploy new software and updates. Smaller and more frequent deploys reduce the risk of each update. Overall, a well-managed DevOps process will mean you have less downtime and higher availability of your systems because smaller deploys are less likely to cause problems. This also allows for seamless deployments and helps your team maintain less-disruptive schedules.

Test and Assess

Finally, testing and monitoring makes sure that problems are caught and fixed early in the development process. It also helps ensure software is functional, business requirements are met, and all parties are getting the results that they agreed to. There are many kinds of testing that you can add to your automated deployments—application functionality, security, and accessibility are good places to start.

DevOps on the new civilrights.justice.gov site

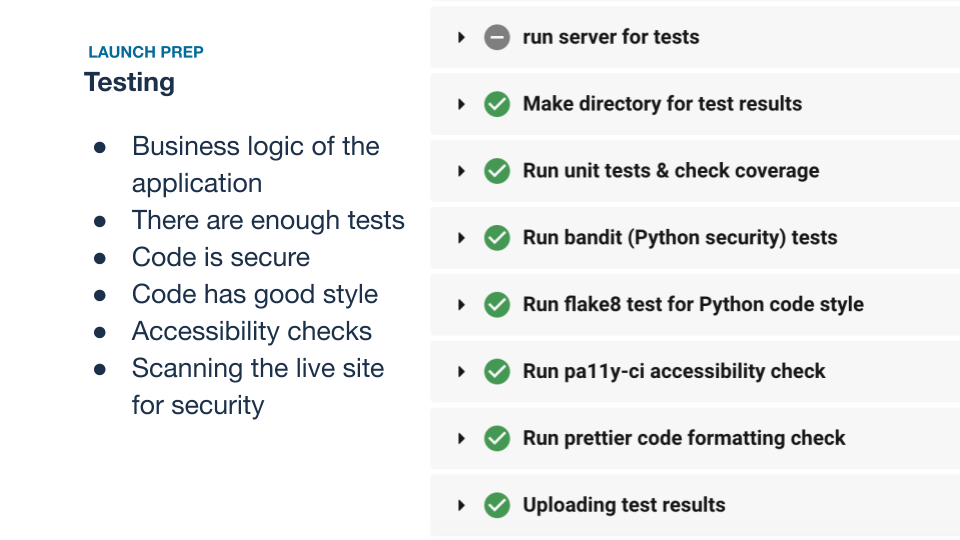

Our overall goal was reduce risk while allowing for faster updates to the DOJ’s civil rights portal. To do so, we wanted to make sure that the team has small, frequent deploys while ensuring proper quality checks. Before we deploy any updates to the site, code goes through three human evaluations and at least three rounds of automated testing.

The DOJ-18F team currently has automated tests for:

- Business logic of the application

- Coverage (whether there are enough tests)

- Security

- Ensuring code is written and formatted to an industry standard

- Accessibility

Automated testing doesn’t replace the need for people with context who approve new work, but it does reduce the risk of introducing errors or vulnerabilities. It can make sure certain bugs are not reintroduced, catch common security vulnerabilities, and accessibility errors.

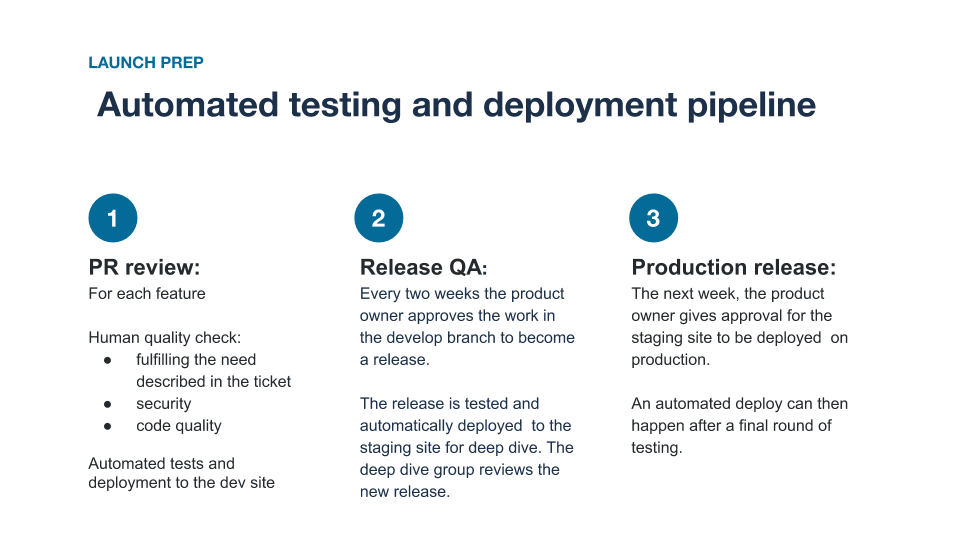

Step one, PR review:

User stories are broken down into development tickets. These tickets will be more detailed with design and implementation components.

Someone creates process, code, or app changes as described in a ticket. After that standalone task or story from a ticket is completed, that portion of code is proposed as a pull request. See this PR documentation for a complete list of checks for PR review.

It ensures:

-

Human quality check for:

- Fulfilling the need described in the ticket

- Security

- Code quality (making sure it is understandable so that future O&M is easier)

-

Automated tests for:

- Important business logic requirements should be captured in tests

- Key functionality should be checked with tests

- Making sure changes fit the security baseline

You can see the code base, including how we do tests at automated deployment on Github. Using cloud.gov helps to keep the deployment process simple, secure and low maintenance for developers.

Step two, Release QA:

Releases are created every two weeks as part of the two week sprint cadence. Product owners and managers approve the work in the development branch to become a release.

The team then spends a week on quality assurance (QA). Generally the reviewers check if the release matches the acceptance criteria, if there are unusual bugs or inconsistencies and you should be ready to bring in the relevant business interests to approve.

Automated tests are run on any code corrections via a PR and PR review to the release branch.

Step three, Production release:

Once user sign-off is done, the product owner or their designee gives final approval of the staging site and then deploys the release to the production environment.

The release is merged into the development branch to make sure any of the adjustments in staging are also accounted for upstream.

Creating a release branch triggers the final run of the automated testing suite. If this is successful, the code is deployed automatically.

A successful deployment is communicated to the team, and there is an opportunity for a quick check to make sure the release went smoothly.

Contingencies

Bugs and flaws are normal in every project, and sometimes they will make it through even the most rigorous review processes, the important part is having clear plans to deal with them when they arise. When critical bugs or flaws are found in production for the civil rights portal, a business owner or their designee will request a hotfix. Once the solution is identified, the hotfix will undergo PR review and QA simultaneously. The branch is then merged into the development branch. Once automated tests pass, there is a quick round of QA, then the code is merged into the upcoming release. This auto-deploys after tests with a short QA period. Then the code will be merged into master, which will also auto-deploy after tests.

In conclusion

Using agile and DevOps and agile parties agree on measurable outcomes

Instead of pages of opaque implementation details that only a few people can understand that are generated through traditional processes, agile and DevOps processes provide concrete, measurable outcome goals and continuous testing will help ensure that you are meeting those outcomes.

If you are working in government and procuring services, you will want to incorporate your DevOps goals into your acquisitions process and putting these standards into your Quality Assessment Surveillance Plan (QASP) can help bake these practices into your projects.

There is more information and context for decisions when they are getting made

Making decisions based on usability testing will lead to a better product.

Course corrections can be made quickly, with fewer bureaucratic bottlenecks

There are many, many unforeseen circumstances that even the best change control board and the best 5-year plan won’t be able to foresee. If you were making plans in 2018 for what you needed in spring of 2020, you wouldn’t have predicted how COVID-19 would change the needs of your organization and products. Instead of futilely attempting to predict the future, we can set up our organizations and products to adapt to change.

If you are in government you need to account for change control, but the good news is that if you are using Agile and DevOps, you already have a sophisticated change control process! You have already worked with the security team to set up baselines and testing requirements and you reach out to them with updates, changes, as well as going through your ATO process which should define when security checkpoints should occur. You can document that process and name that document “Configuration Change Control” and you’ll have satisfied your change control requirements!

Change is hard

You probably can’t move all of your projects to an agile DevOps model at once. Instead, try piloting with one project: Make adjustments on how that process works based on the lessons learned from the pilot. Then expand what you’ve learned to a small number of other projects. At that point, you can formalize the processes and create informed policies. Continue to add more projects as they are ready. Your giant legacy projects may not be ready for agile or DevOps anytime soon, but change starts one step at a time. Keep moving forward towards those goals and look for opportunities to shift the organization towards better practices.