In 1986 a nuclear reactor known as Chernobyl released harmful radioactivity which spread over much of the western USSR and Europe. The core of this reactor remains a glowing, ineradicable mass of deadly radioactive lava in the middle of a large Exclusion Zone unfit for human habitation.

The Chernobyl reactor core could not be removed. It was and is too big, too hot, and there is no where for it to go. Instead, it was entombed in a concrete sarcophagus where it will radiate harmlessly for decades if not centuries. This was unfortunately the best outcome that could be achieved. In the software industry, I’ve often seen this same approach used with legacy software systems. I call it The Encasement Strategy.

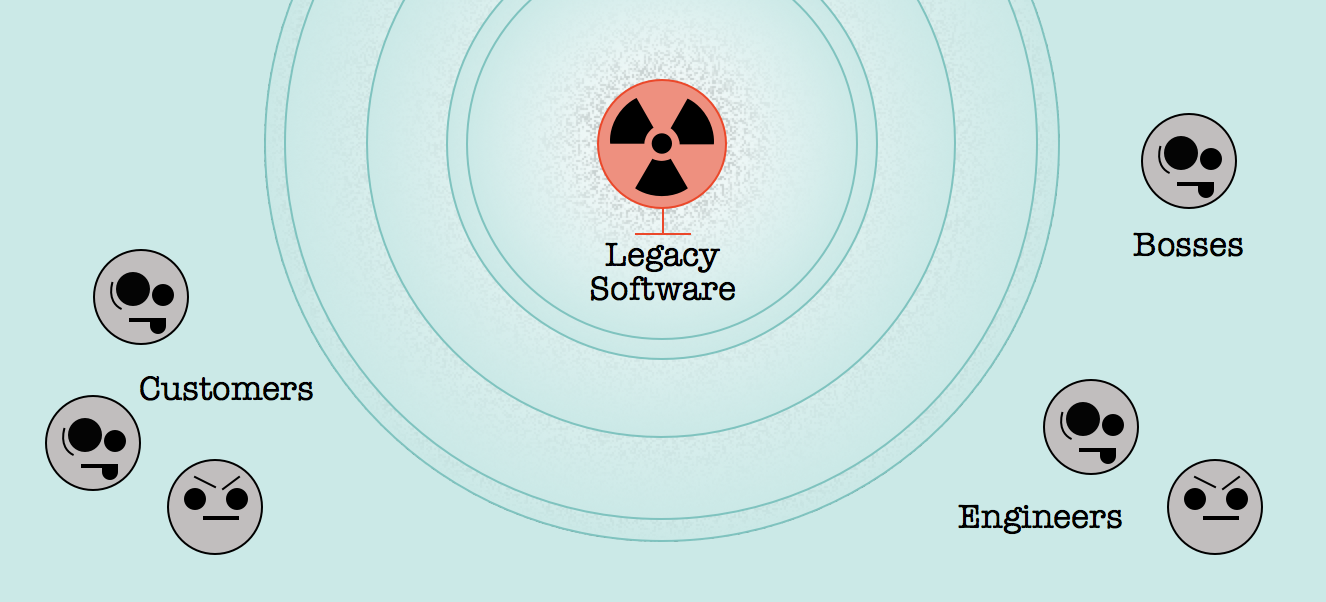

Legacy systems make everyone that has to touch them queasy, from the software engineers to the managers. But most especially there comes a time when the system no longer serves the most important constituent of all, the customer. This not only contributes to inefficiency, but can sometimes have detrimental effects on the users of a system.

Like Chernobyl, these systems are toxic; but unlike a power plant, what they once produced is not fungible with other sources. There is often no replacement for the legacy system.

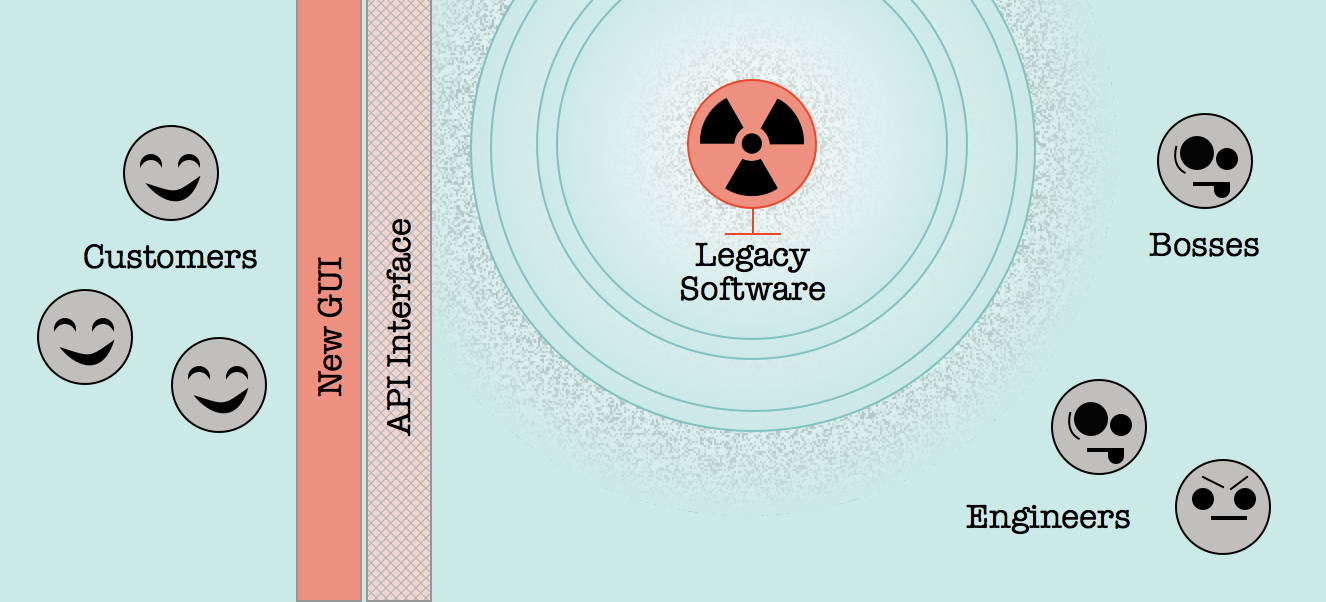

The basic mechanism for remediating such a system comes straight out of Computer Programming 101: you create a well-designed interface. In modern terms, this is an Application Programming Interface or API. That term API used to be more general, but now it almost always connotes a web-based interface accessed through HTTP and usually using JSON as its data format.

An API is an inter-face, a face, a façade or a wall between. It allows the user blissful ignorance of what precisely is behind the wall. You need only worry about what comes and goes through the gate. What lies beyond—whether it’s magic, or a red-hot mass of legacy code—is no longer the user’s concern.The customers on the user side of the API are protected from the toxins, leaving the engineers to deal with implementation.

There is something magical about this basic act of defining an interface. To paraphrase Buckminster Fuller, to define is divine. It creates something simple and understandable from nothing, something you can grab onto, something solid.

By defining an API, you can begin to immediately serve the customer, because you can build a modern GUI on top of it, unencumbered by the legacy of the past. You can begin to build what history has shown needs to be built to serve the customer, whether that is the US citizen at large, or a division of an office, or a bureau of an agency. You may choose to allow outsiders to directly make calls to your API, but even if you do not do this, you can create independence of the legacy technology.

Sometimes, such an API can be constructed based on a clear engineering understanding of the internals of the legacy system. This is the best approach; however, it may be impractical if the knowledge and understanding of the system has been lost. In such a case, programmers are wont to resort to reverse engineering solutions, as I did recently. Any system which offers a GUI (graphical user interface) to users can be reverse engineered to construct a programmatic interface on top of that interface. We generally call this scraping the GUI, and it isn’t pretty. It leads to the absurd architectural diagram of a GUI on top of an API on top of a GUI on top of a miasma. But it gets the job done, and that is what a pragmatic software engineer must care about: serving the customer.

Once a valuable API is defined, there is a wall between decisions about how to effectively use the API that completely divorces them from decisions about what to do with the code that implements the API. Efforts to rewrite the legacy system may proceed mostly independent of the efforts to build functionality that uses the API. Or, efforts to rewrite it may not proceed at all—the Encasement Strategy.

As an engineer who loves hard problems, the idea of leaving a legacy system in place and not attempting to rewrite it is a serious challenge. But I think we should always make that decision independent of decisions on how to best serve the customer.

Let us work through a highly contrived thought experiment. Imagine that 100 years from now there is a team of 5 highly skilled specialists, known as Software Conservationists. Their sole job is to maintain the sealed-off core of the legacy system which is STILL implementing an API that serves the US Citizen. Just like Art Conservationists working at the Smithsonian today, future citizens could train to do it.

The Software Conservationists are employed because of two decisions made today:

- A decision to create an API

- A decision not to rewrite the legacy system

Let us say that it costs $1,000,000 present-day dollars to maintain this team every year from now until the corium in Chernobyl is no longer hot.

How much money would you have to save this year in order to justify paying out an annuity of $1,000,000? Assuming that one could obtain a risk-free 3% after-inflation return on an investment (or, in accounting terms, discount rate of 3%), how much money would you have to save to justify making a decision today that creates the Software Conservationists profession a century from now? The answer is an elementary present value calculation: $34 million or more.

If a realist who is keeping her users top of mind can save the US Taxpayer $34 million today, she should employ the Encasement Strategy and not be ashamed of it. Such a realist should of course recognize the long-term effects of Software Conservation versus the creation of a new, modern system.

Whether the details of your toxic system lead you to begin the legacy rewrite immediately or to employ the Encasement Strategy of delaying the rewrite indefinitely, get started on a well-designed API today.

Postscript

After this article was published, a kind tweet by David Illsley suggested that this was the Strangler Pattern which Martin Fowler has blogged about. Martin Fowler credits a paper by Chris Stevenson and Andy Pols as the initiator of this idea, and further more references a set of case studies collected by Paul Hammant.