The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is civil rights legislation that protects people with disabilities from discrimination.

We worked with a team at the Department of Justice to redesign ADA.gov. We helped them launch beta.ada.gov, and we’ve designed new content for some of the most sought-after ADA topics.

Anyone who has written, or read, legal content knows that legal writing is some of the most complex and nuanced writing you’ll ever come across. Legal writing is often full of technical jargon, laden with symbols and punctuation, and resistant to plain language revision.

While working on beta.ada.gov, our content team confronted another common feature of legal writing: legal terms are broadly defined. Because authors of a given law or regulation cannot possibly predict the unique circumstances of every situation to which the intent of law might be relevant, the wording needs to offer flexibility so that it can apply to a variety of situations. This flexibility is reflected in the way a legal definition is framed—on its face it seems to lack specificity, but its meaning becomes tangible when applied to a real-world example. This occasional lack of specificity is a feature, not a bug; it offers flexibility for the law to be applied in multiple circumstances, many of which are impossible to predict. It might protect someone’s rights in an unforeseen situation.

This important feature of legal writing that allows the law to be applied in unforeseen situations also makes it challenging to write clear, actionable plain language content. This was the tension we encountered when designing content for beta.ada.gov: writing for action and flexibility.

How we started

Product vision

Our first task was to determine the purpose of ADA.gov content. The most direct expression of that purpose came in the form of a product vision:

Empower users to voluntarily comply with the ADA or to understand their rights and the rights of others by providing up-to-date resources based on contemporary user needs.

Our goal was to design content that embodied that product vision. We would attempt to write clear, plain-language content that empowered users to understand their ADA rights and obligations, and evaluate existing content according to its alignment with the product vision.

Research

We examined analytics, consulted with staff from the ADA information line (a DOJ operated toll-free telephone line the public can call with ADA questions), and set up user research interviews with the hope of better understanding which ADA topics were of the highest public concern.

Our research confirmed what many in the Disability Rights Section at DOJ already knew or suspected. There was one topic with the most interest from the public: service animals.

Prototyping

Using Federalist (soon to be cloud.gov Pages), we were able to rapidly design and deploy a prototype for service animal content. We wanted to design content that aligned neatly with the product vision, but we also knew that we couldn’t answer every question anyone might have about service animals. We understood that if we tried to do that, the content would be too dense to be useful (not to mention become an additional maintenance burden).

With this in mind, we attempted to write clear and actionable content that would communicate information about the ADA as directly and concretely as possible.

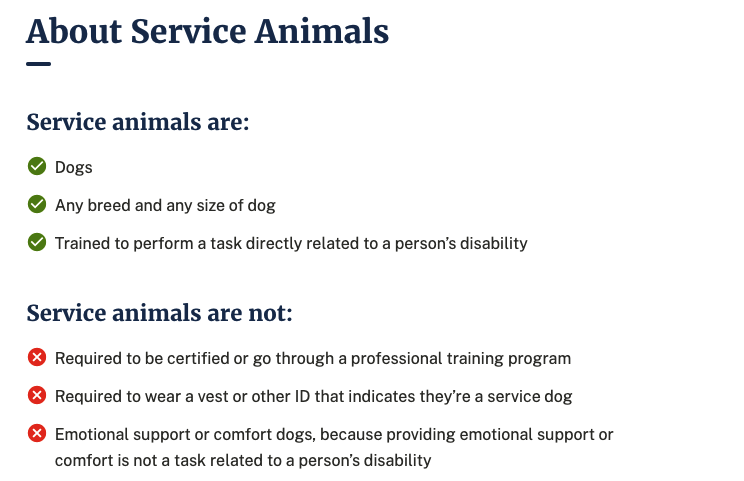

Here are two examples of that direct communication:

Writing for action and flexibility

Returning to the product vision — the foundation for the ADA.gov content strategy — we wanted to empower users to understand their rights and obligations under the ADA. To do that, we needed to tell users as clearly and directly as possible what the ADA requires. This is hard, because some definitions in the regulations are intentionally broad for purposes of flexibility.

For example, take the term fundamentally alter. The ADA regulations specify the following regarding service animals:

The animal can only be removed if it engages in the behaviors mentioned in § 36.302(c) (as revised in the final rule) or if the presence of the animal constitutes a fundamental alteration to the nature of the goods, services, facilities, and activities of the place of public accommodation.

So, what “constitutes a fundamental alteration to the nature of the goods, services, and activities of the place of public accommodation”? It’s impractical for the Department of Justice to define how this term applies to every business practice or even every new technology or other social change that may arise. So the term, like many other legal terms, is broadly defined. So how do we write content that preserves the flexibility of the definition, but offers as much specificity as possible?

Use examples

We decided that the best way to convey more specificity while avoiding being over-prescriptive was to use examples. Here’s the example we used for the term fundamentally alter:

In most settings, a service animal will not fundamentally alter the situation. But in some settings, a service dog could change the nature of the service or program. For example, it may be appropriate to keep a service animal out of an operating room or burn unit where the animal’s presence could compromise a sterile environment. But in general, service animals cannot be restricted from other areas of the hospital where patients or members of the public can go.

This example helps illustrate how the law might apply in a specific situation—making it more tangible for the reader. It’s a map to help the user situate themselves and their circumstances in the context of the law. It is descriptive without being prescriptive.

Collapse complexity

We didn’t want to force users to read content that isn’t relevant to them, so when we included extra detail or definitions, we used accordions, or other collapsible design patterns.

This technique was useful for instances where we couldn’t sufficiently explain the ADA without defining a term in the law or regulations. It was also useful for examples and further explanations, such as the difference between service animals and emotional support animals.

Test with users and iterate

We pulled data from analytics and consulted with the information line team, but there’s no replacement for usability testing. We tested the content multiple times, in multiple phases, with a variety of audiences. We learned more with each session, and we continued to iterate. The content is never completely done; it must change with the needs of users. We made it a priority to test the content with people with disabilities at every phase, understanding that we couldn’t be successful unless we designed with — not for — people with disabilities.

The work continues

Our partners at the Department of Justice continue to iterate on the site, developing new, plain-language content that aligns with the product vision and incorporates user feedback. The challenge continues as well: writing for action while avoiding oversimplification of the law. It’s among the most difficult and rewarding aspects of writing in a legal context.

18F launch team: Allison Norman, Michael King, Laura Poncé, Ryan Johnson, Joe Krzystan, Olesya Minina, Aviva Oskow, Kevin Mori, Brian Hurst, Austin Hernandez, Rebecca Refoy, Miatta Myers, Norah Maki, and Colin Murphy